The digital art center

What is the History of the NewArt Centre?

The NewArt Centre is one of the main projects of the NewArt Foundation, a non-profit organization committed to the preservation, study and promotion of digital and technological art. The foundation was born in 2003 thanks to the initiative of Marie-France Veyrat, artist, Andreu Rodríguez Valveny, entrepreneur in the technology sector, and the art critic Arnau Puig, with the aim of giving visibility to new forms of creation linked to technology.

In 2006, the collaboration with the ARCO Madrid fair led to a decisive encounter: the incorporation of Vicente Matallana, a pioneer of technological art in Spain, which strengthened the international projection of the foundation.

For more than a decade, the NewArt Foundation has been present at the main events and institutions dedicated to digital arts and innovation: Ars Electronica, ISEA, Sònar, B3 Biennale, V2_ Lab, as well as projects in collaboration with research centres and universities: Eurecat, the Technology Centre of Catalonia, HacTe, the Art, Science and Technology Hub of Barcelona, Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC), Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV), art centres and museums. The New Art Foundation has Framework Collaboration Agreements with more than 10 national and international institutions, and participates in a European consortium within the framework of a CREA-CULT programme of the European Union.

Since its beginnings, the foundation has focused its activity on the research, production, cataloguing, exhibition and conservation of works created with technology, while also supporting artists who experiment with emerging digital languages.

Over the years, the foundation has built one of the most unique technological art collections in the world, with pioneering works from the late 1960s to the present: generative art, interactive installations, robotic works, software art and projects that have marked a before and after in the history of digital arts. The works have been acquired at international fairs and galleries, through commissions, collaborations with artists and donations, under the criteria of a jury of experts in technological art.

The growth of the collection and the increasing public interest in digital art made it clear that there was a need to create a space where these works could be shown, experienced and understood in all their complexity.

This is how the NewArt Centre was born, opening its doors in 2025 with the aim of offering an immersive and futuristic museum experience.

What exhibition and museum experience can we find at the New Art Centre?

Hello World!, the inaugural exhibition of the New Art Centre, is a journey through 60 years of technological art history through our collection: a look at the past and present, as well as a projection toward a future full of challenges.

Although the foundation has been working for many years, we are beginning a new stage in which the presence of the public is essential. Moreover, Hello World is the first phrase taught when learning to program in computer science courses.

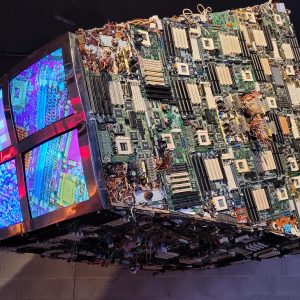

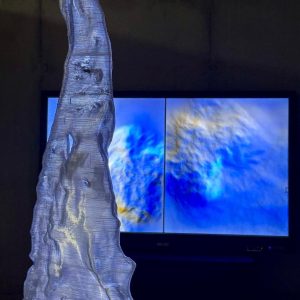

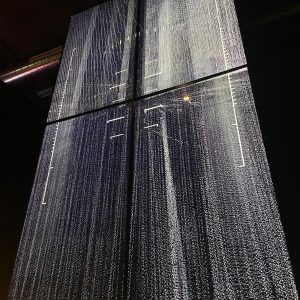

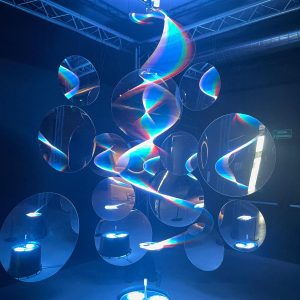

The exhibition features 30 works of technological art that address various concepts: the fine line between the digital and physical worlds, programmed obsolescence, outer space, black holes, the moon, the relationship between the body and physical space, and the three-dimensionality of light.

Various technologies are used, such as screens, projectors, computer boards, robots, generative software, light and sound effects…

The exhibitions will change periodically, and visitors will be able to see new works and new museum routes.

The centre is not just an exhibition space: it is a living ecosystem, where technology, creation and innovation coexist to generate knowledge and culture.

Why is the centre so unique?

In the field of technological art, most international institutions —such as ZKM in Karlsruhe, Ars Electronica in Linz or V2_ Lab in Rotterdam— are entirely public centres, funded by governments, universities or large consortia. This is the predominant model because digital art requires significant resources, technical infrastructure and specialised teams.

The fact that the NewArt Centre was created by a family is exceptional and unique in Europe because it demonstrates a vision that is pioneering, an extraordinary cultural commitment and a long-term dedication that has made it possible to create a project that today is embraced by the public.

The other characteristic and unique element of the centre is its clear vision of going beyond a simple exhibition space. The storage and workshop areas are key spaces in the centre because they ensure the proper conservation of the collection, allow for innovation and the production of new works, demonstrate that technological art is a process rather than just a result, and offer visitors a unique and memorable museum experience.

All this knowledge and experience acquired over two decades is placed at the service of the artistic community through the centre, in order to promote technological art at its highest potential and return it to society in the form of culture.

Why Reus?

The location of the NewArt Centre in Reus is not accidental. The city has a long cultural tradition, a recognised creative vitality and an innovation network that position it in a moment of expansion.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude:

- To the patrons, collaborators and public institutions, for their trust and for making possible the preservation and expansion of this unique collection.

- To the trustees of the NewArt Foundation, for their dedication, vision and perseverance over two decades.

- To the media, for contributing to the dissemination of digital art and giving a voice to a project that seeks to bring technological culture closer to all citizens.

Without all of them, this project would not be the vibrant reality we present today.

Digital and Technological Art

What is Digital and Technological Art?

Technological art —also known as digital art, new media art, electronic art or interactive art— arises from the encounter between artistic creativity and technological innovation, and very often scientific research. Technology can be interactive, immersive, experimental or electronic. It can incorporate sensors, light, sound, artificial intelligence, robotics, virtual reality…

Digital art is any artistic work created with computers or digital tools. The main medium is not physical (paint, stone, canvas), but bits and software. Artistic creation is carried out with digital tools and processes such as design software, 3D illustration, animation or generative art.

It does not appear suddenly, but is the result of various historical evolutions that converge throughout the 20th century.

Which artistic movements precede digital and technological art?

Dadaism (1916–1924)

Heritage: chance, play, the breaking of rules.

It breaks with the idea of a fixed artwork and introduces unpredictable processes.

It is key because it opens the door to generative systems and artistic algorithms.

Constructivism and Suprematism (1913–1920s)

Heritage: geometric forms, rationality, structure. They are predecessors of computational art, as they introduce the idea of a rule-based visual language.

Bauhaus (1919–1933)

Heritage: integration of art, design and technology. It opened the door to conceiving technology as a creative tool and art as a modular and experimental system.

Kinetic Art and Arte Programmata (1950–1960) (exploration of new tools)

Heritage: movement, light, mechanical and electronic interaction. Movements such as GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel) explore public participation and perceptual systems — a clear precedent for digital interactivity.

Op Art (1960s)

Heritage: perception, optical illusion, repetitive patterns. It introduces the idea that the artwork can activate and alter the visitor’s perception, a conceptual basis for many contemporary immersive installations.

Fluxus (1960s)

Conceptual Art (1960–1970) (arrival of computers)

Heritage: the idea above the object. Essential for technological art, where the code, the system or the device are part of the idea, not a traditional object.

Cybernetics and Systems Art (late 1950s–1970)

This is the most direct precedent.

Heritage: feedback, self-regulating systems, interaction between artwork and audience. Artists such as Nicolas Schöffer or Jack Burnham introduce concepts of living and technological systems that would define digital art.

Video Art (from 1965 onwards)

Heritage: electronic image, devices, signal manipulation. Nam June Paik and other pioneers opened the door to the use of electronic devices as an artistic medium.

Computational Art (since 1960)

When the first computers capable of generating graphics appeared, the following emerged: algorithmic art, generative art, computer-generated graphics.

Pioneering artists and engineers such as Vera Molnár, Frieder Nake and Michael Noll were already programming works with code long before personal computers existed.

The digital and multimedia revolution (1980s–90s)

With the personal computer, the Internet and digital video, interactive art became popular: installations with sensors appeared, and image, sound and programming merged, giving rise to the culture of multimedia. This is when technological art shifted from scientific experimentation to the international artistic scene. Foundation of the Ars Electronica festival.

Net Art and Digital Art (1990–2000)

With the Internet and personal computers, the following emerged: net art, interactive art, multimedia installations, pioneering virtual realities.It is the direct bridge to today’s technological art.

21st century: technological art enters museums and society.

With digital maturity, technological art has evolved into: advanced generative art, artificial intelligence and machine learning, immersive installations, virtual and augmented reality, complex interactive systems.

IN GENERAL SUMMARY:

Technological art draws from: – Systems (cybernetics) – Code and algorithm (computational art) – Participation (Fluxus, kinetic art) – Light and perception (Op Art) – Movement and technology (kinetic art, robotics) – Ielectronic image (video art) – Popen processes (conceptual art, Dadaism)

Just like the paintbrush or the camera, code, sensors and machines become creative tools used by artists to express their emotions and reflections. Technological art is born from the desire to explore the creative possibilities of technology. Art reflects society, and our society is technological.

Is digital art relevant in the art world?

Is digital art a growing art category?

The digital sector (immersive installations, AI-based works, data art, etc.) is one of the fastest-growing fields in art fairs, institutions and commissioning programmes. It is not only culturally relevant: it is also a significant economic segment of contemporary art.

Major museums —MoMA, Tate, Pompidou, ZKM, LACMA…— are increasingly incorporating digital works into their collections.

Centres such as V2 or ZKM and festivals like Ars Electronica specialise exclusively in digital and technological art.

Large biennials, museums and international institutions regularly include digital projects. This shows that it has moved from being “experimental art” to becoming mainstream art.